Icarus in Flight is an original chamber work by composer Richard Festinger in collaboration with The ClimateMusic Project. It explores three human drivers of the climate crisis–population growth, carbon emissions, and land-use change–over two centuries, from 1880-2080.

The award-winning Telegraph Quartet performed this new work at its premiere at the Noe Valley Ministry in San Francisco in June, 2018.

The title of my quartet offers a metaphor for the trajectory of climate change. Imprisoned by King Minos on the isle of Crete, the brilliant Athenian craftsman Daedalus fashioned wings of feathers fixed with wax for himself and his son Icarus, so to escape from the isle by flight. Daedalus warned his son against flight too low or too high, to avoid both the ladening dampness of the sea and the wax-melting heat of the sun. Elated by the thrill of flight, Icarus ignored his father’s admonitions, venturing high into an environment too warm to sustain him.

–Richard Festinger

The work is comprised of three large sections played without pause: the first representing the years 1880 to 1945, when the data are growing slowly; the second from 1945 to 2015 when growth accelerates exponentially; and the third from 2015 to 2080.

One year of historical time occupies about 9 seconds of musical time.

~Population growth controls the average density of musical events over time. In this context, density means the number things that happen in a given time period.

~Carbon emissions control the frequency range of the music, from lowest to highest pitch, increasing gradually from a perfect fifth in the middle register to a span of 6.25 octaves, before collapsing to almost nothing.

~Land-use is represented by the increasing proportion of music that is played with specialized timbres (tone colors), including mainly rapid tremolo bowing, bowing close to the bridge (producing a brittle metallic tone), and pizzicato (plucking the strings).

In the last section, our future, the controlling data alternate between two greenhouse gas concentration scenarios developed by the Inter-governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a scientific body under the auspices of the United Nations.

Human Drivers, Human Choices

The composition focuses on 3 key human drivers of climate change: CO2 emissions, land use, and population growth.

CO2 Emissions

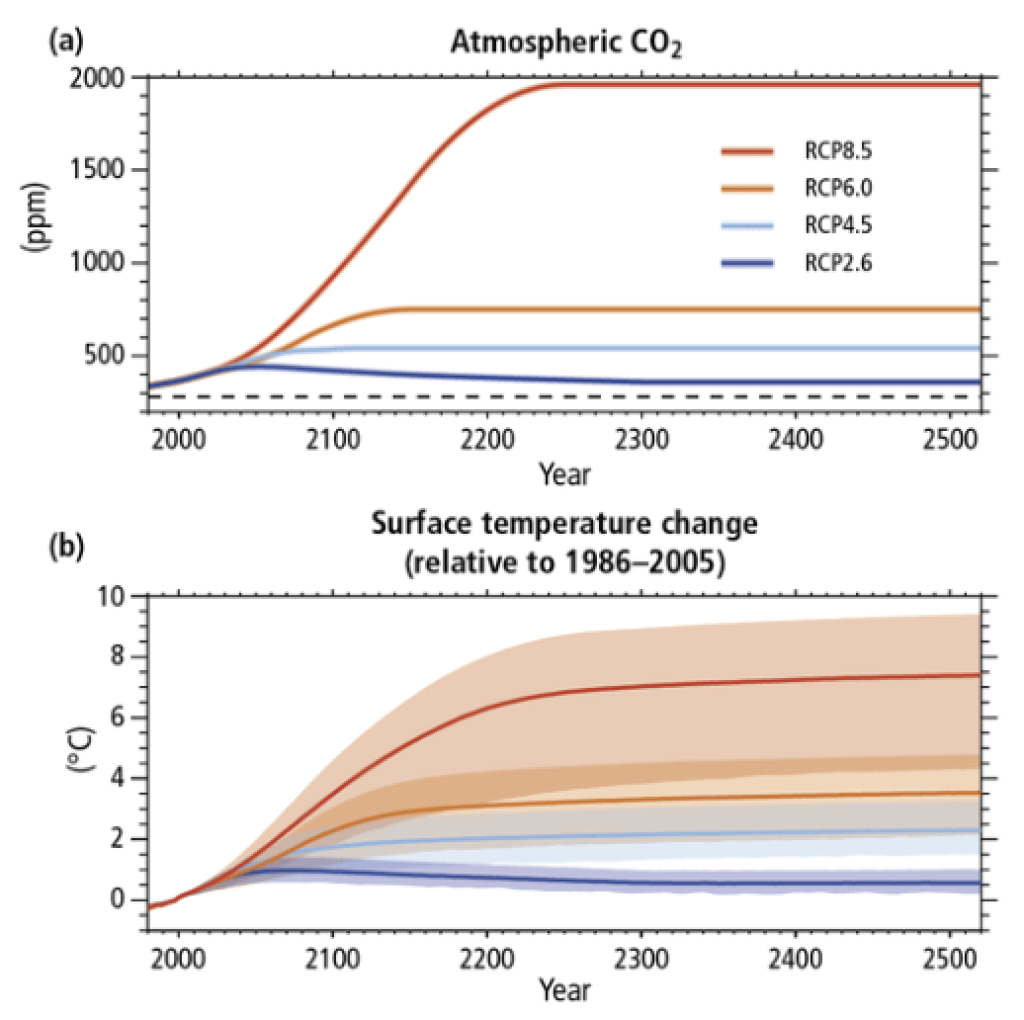

The two scenarios referenced in Icarus in Flight represent an extreme high warming path (RCP 8.5) and a path with mitigation action (RCP 2.6). They are named after the amount of extra solar radiation that is retained by the Earth (8.5 and 2.6 Watts/m2, respectively).

The path with mitigation action would limit the temperature increase from pre-industrial levels to below 2ºC (3.6ºF), while on our current path, average temperatures could rise over 5ºC (9ºF) by 2100.

The figures show the future atmospheric CO₂ concentrations and range of global surface temperature changes associated with each RCP scenario [1]. The red line represents a future in which we continue business as usual; The indigo represents one in which global collaboration and climate action limit average global warming to less than 2°C.

The Paris Agreement set 2ºC global warming as the upper target, with a preference for 1.5ºC, to avoid irreversible impacts. If sufficient action is not taken in the near term, it is a scientific certainty that these thresholds will be exceeded.

WHY 2ºC?

The final third of Icarus in Flight alternates between two starkly different futures. The pitch oscillates between different levels of CO₂ emission – one that limits warming to 2ºC or less, and one that soars above this crucial threshold.

Human activity has already warmed our planet by 1.1ºC (2ºF) globally, and this increase has had noticeable and dangerous impacts on climate and human health. We have already seen increasingly severe heat events that have resulted in human mortality, rising sea levels, more destructive tropical cyclones and increased area burned by wildfires. [2]

If global temperature were to rise higher, we would see increasingly severe environmental degradation and threats to human life. If we can limit warming to 2ºC or lower, we can avoid some of the worst, irreversible impacts of climate change.

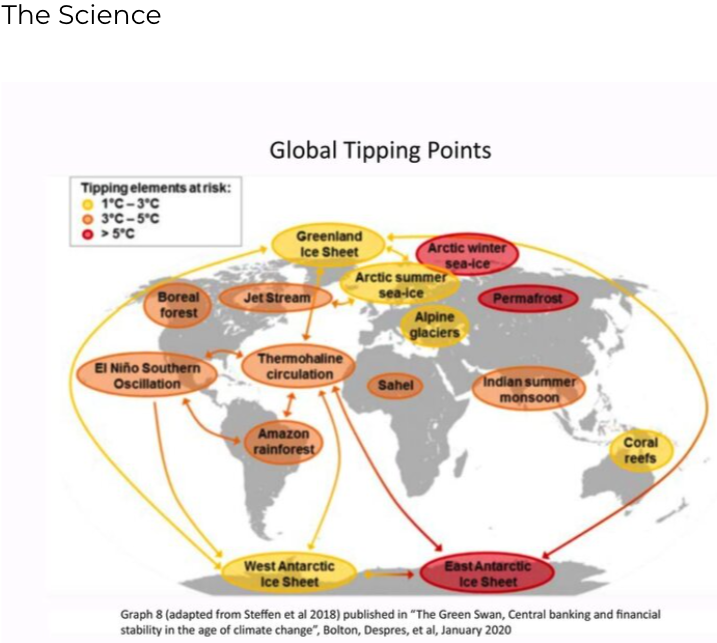

Why then, one might ask, is 2ºC such an important target? An example lies in aptly named “tipping points.”

EXAMPLES OF TIPPING POINTS

| 1.5ºC OR 2.7ºF | 2ºC OR 3.6ºF | 3ºC OR 5.4ºF | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Permafrost Impacts | 17 – 44% reduction in permafrost | 28 – 53% reduction in permafrost | Potential permafrost collapse |

| People exposed and vulnerable to adverse effects of crop yield change | 8 million | 81 million | 406 million |

In our complex climate system, when we add too much energy to the system by combusting fossil fuels, using land poorly, and not consuming sustainably, we trigger tipping points.

Triggering these tipping points results in far more severe consequences than if we were able to reduce warming by even just half of a degree as you can see from the examples above.

Some tipping points can even reinforce global warming in what is called a positive feedback loop. For instance, when permafrost thaws, CO₂ stored in frozen soils is released, which can then trigger further warming. It is estimated that permafrost currently stores twice as much CO₂ as our atmosphere currently contains [all from 3].

Related Content

More on other tipping points in various locations and at various levels of warming.

Alisa Singer’s artwork on tipping points. (Below)

How does Land Use Tie in?

Land can function as a source or a sink of greenhouse gases including CO₂ depending on what we do (or don’t do) with it. Change in land has mostly consisted of conversion of natural landscapes to human use – currently, more than 70% of global ice-free land is directly affected by human use.

Global population growth in tandem with per capita consumption of food, energy, timber, and fibre has driven increasing land and freshwater use. Agriculture, forestry, and other land use alone accounts for 23% of GHG emissions.

Natural land, however, can work as a sink of carbon emissions – from 2007 – 2016, natural land processes absorbed about 30% of CO₂ emissions. Because of this, more efficient land use and altering our consumption patterns is key to mitigating climate change.

For instance, from 2010 – 2016, 25-30% of food produced was wasted globally and accounted for 8 – 10 percent of GHG emissions. Eliminating this loss could reduce greenhouse gas emissions while freeing up land for climate adaptation projects that produce green energy or serve as carbon sinks. [all from 4].

Related Content

IPCC Newsroom Article with more detail

What about Population?

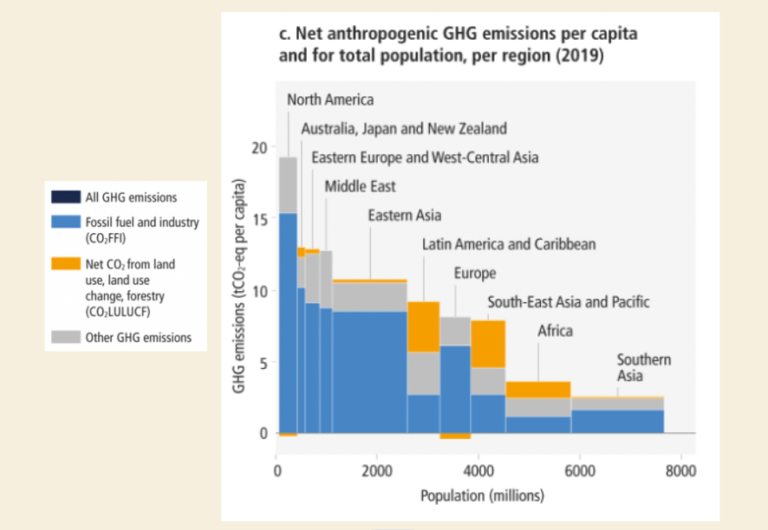

It’s not necessarily the size of the population that matters most, but how much energy is spent per person, or per capita resource consumption.

Earth’s human population will grow, and we need to plan for it. By using our resources more efficiently, we can secure enough food for everyone, and enough resources for developing countries to build infrastructure.

By reducing per capita resource use alongside adopting efficient land management, we can ensure that our inevitable population increase does not offset our progress in reducing emissions.

As we can see in this figure [5], there is a global disparity in resource use per capita, with regions containing wealthier, more developed nations generally emitting more greenhouse gases per capita. Reducing resource use in wealthy nations and assisting developing nations with building clean energy infrastructure to meet their growing needs is key to striking a balance that works for our planet.

Additionally, supporting family planning and quality education for everyone, everywhere would substantially reduce poverty and improve gender equality.

Such investments would improve access to economic opportunity, delay childbearing, decrease child and maternal mortality rates, and prevent unintended pregnancies.

These investments would also help us progress towards our climate goals by slowing population growth in a way that benefits everyone.

Related Content

Check yourself with this personal carbon footprint calculator

Learn more about the societal and climate impacts of family planning and education

Read Project Drawdown’s Solutions Table

Listen to “Everything Matters” by Khafre Jay

Getting to 2ºC or less

In order to limit average global warming to 2ºC or less, we will need to reduce emissions by 25% by 2030, and achieve net zero CO₂ emissions by 2070 [6].

Project Drawdown, linked in the related content box, provides detailed estimates for CO₂ reduction associated with different forms of climate action and policy, and how we can use them to limit warming to 2ºC or less.

It can be overwhelming to think about tackling the issue of climate change on top of all of the other problems we face, including global poverty, racial injustice, and income inequality. Thankfully, many of the most impactful solutions that we can use to achieve our climate goals will help us in other areas as well.

Below, we’ve included resources so that you can get involved by learning more, volunteering, and donating.

Sources: [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6]

Action Ideas and Resources

Click on links for information

- Read about “multi-solving”

- If you are a US Citizen, find your city here for upcoming local elections

- Listen to The ClimateMusic Project’s podcast episode highlighting equitable solar

- Learn about the climate and health benefits of walkable cities

- Call your senator or local representative using this script to express support for equitable solar

- Find a local community garden or food pantry and get involved

- If you live in the US, check learn about financial incentives to make your home energy efficient

- Learn more about what you can do with on the ClimateMusic action page.

Image credit: Mark Pearsall/Arup