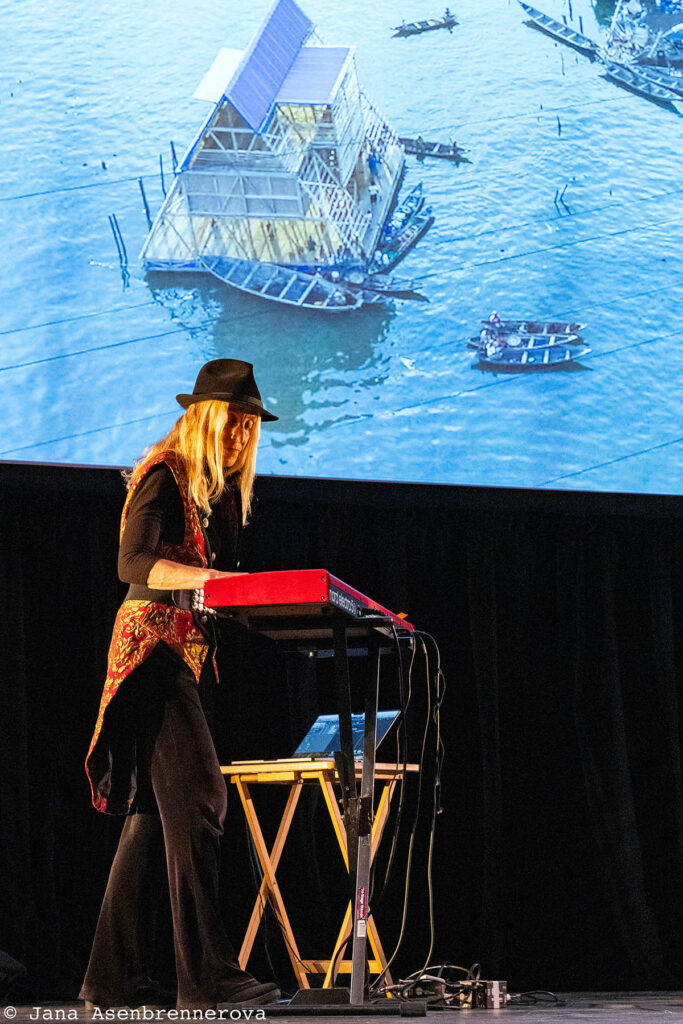

What if We…? is a 10-minute composition by Wendy Loomis with spoken word by Royal Kent in collaboration with ClimateMusic Project. It explores climate and sea level rise during this century and premiered at a World Bank event in Washington, D.C. in 2019.

Through the droning timpani and the C minor chord structure, the beginning of the piece introduces the ominous quality of the future due to climate change – and specifically with sea level rise.

The melodic theme continues and is then overtaken by sound bytes from newscasts from around the world announcing specific devastation due to sea level rise. Following the newscasts section, the sonifications enter representing ‘business as usual’ and thus the worst case scenario. The sonifications gradually become more strident, louder, and chunkier.

Simultaneously with the sonifications, there is a battle between the bass and the drums. The bass plays a short solo and is representative of land area. Gradually, the drums take over (drums representing the rising sea level) to the point where the melodies of the keyboard and bass are completely overrun by the drums.

A dramatic break occurs when the drums crescendo and then stop. There is an entry of the piano and bass in a sweet melody surrounding voices singing in a poignant plea: “What if we – what if we – what if we – change?”

The music then shifts to a slow gospel-like feel, lightly syncopated representing the possibility of change … a touch of hope is felt. The themes move in major key rounds of Bb, A, B and return to Bb. Accompanying this are the sonifications reflecting the mitigation scenario that represent the result of humans making changes.

Royal Kent enters with poem that depicts to the incredible essence of the natural world and how essential it is for us to work to preserve it.

The last part of the piece is a return to the chorus: “What if we – what if we – what if we – change?”

What if we…? tells the story of the effects of sea level rise – a direct effect of warming – on the land area and population affected by 1 in 100 year floods.

The data are represented in the piece in two specific ways: First, we took future climate projections and translated them into plausible news headlines for the year 2045. Second, we used data sonification, a process that converts data to audio files, to reflect the increasing portion of the population and the land area affected by sea level rise. This can be heard as more digitally-derived sounds, including distortion and reverberation, which increase in intensity and choppiness.

The piece follows two possible future scenarios: the “business as usual” case is represented first in the music; then, after a hopeful interlude, the less intense scenario with mitigation action is reflected.

In addition, after you hear the news headlines, we also feature a duel between the drums and bass. In this duel, the bass represents the land mass, and the drums represent the sea. This section starts with a bass solo, and the drums progressively take over – in an approximation of the acceleration of sea level rise – ending with a drum solo.

The Issue at Hand

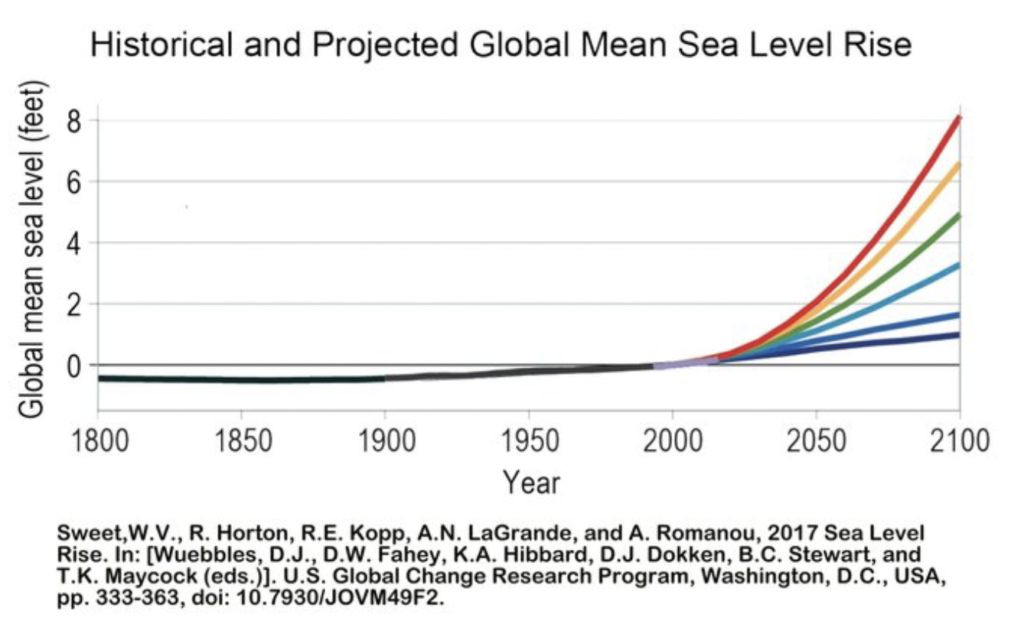

Sea level rise (SLR) is driven by two major factors: melting of land ice, and thermal expansion of water. When land ice melts, it introduces additional water to our water cycle and causes sea levels to rise. When water heats, it also increases in volume. So, as global temperatures increase, ocean water warms and takes up more space, adding volume to our water cycle. This additional water from melting and increased volume of water due to heat both drive sea level rise.

SLR is already underway. Global average sea level rise increased by 20 cm, or about 8 inches, between 1901 and 2018 due to human influence (IPCC AR6). This increase has already had costly impacts – according to Lloyd’s of London, “the approximately 20 centimetres of sea-level rise at the southern tip of Manhattan Island increased superstorm Sandy’s surge losses by 30% in New York alone” (Lloyds).

In this image to the right, it shows Historical and Predicted Sea Level Rise from Alisa Singer’s series of paintings, EnvironmentalGraphiti.

Differences in ocean circulation patterns and height above sea level contribute to different levels of SLR across the globe (source). This means that some cities will see even higher losses than those observed in New York. Urban planners in Miami, as in many low-lying cities, are expecting 5 to 6 feet of SLR by 2100, compared to the global average projection of about 2.5 feet in a business-as-usual scenario. This degree of sea level rise in Miami county would displace about 30 percent of the population, or about 800,000 people.

In this image to the left, the IPCC’s AR4 graphic that inspired this art piece.

Why should we care?

As mentioned above, Miami is an example of a major city that will experience significant displacement due to sea level rise. While wealthy displaced property owners may land on their feet, middle-class coastal residents whose wealth is tied up in their homes could lose generations of wealth-building as a result. On top of this, lower income residents in inland, higher elevation regions of the city could are already affected by gentrification as real estate developers seek higher ground. In a world of severe sea level rise, many cities could face similar fates that worsen pre-existing inequalities and displacement if we don’t implement equitable adaptation plans.

Many other major cities, including Calcutta, Amsterdam, Shanghai, Tokyo, New York, and Houston are threatened by sea level rise. These cities are important hubs of international culture and trade, and sea level rise could damage our supply chain if these and other ports are impacted (source). Additionally, according to the Union of Concerned Scientists, roughly 128 US military installations valued at a total of $100 billion would flood with just 3 feet of SLR. These are just some examples of the financial costs of SLR; as mentioned in What If We…?, rising sea levels could cost the world $14 trillion by 2100.

Additionally, sea level rise will threaten the existence of island nations and flood low-lying coastal areas. About 430 million people, significantly more than the entire population of the US, will be exposed to SLR by 2300 if we don’t take action. Many of these people will be completely displaced from their homes, and become climate refugees. If we use all the tools at our disposal to mitigate SLR, however, this number comes down to 120 million, significantly reducing the negative impact of SLR on humanity (source).

SLR not only affects human culture and life, but also impacts animal and plant life. For example, increased flooding in the Nile Delta region would harm biodiversity, reduce agricultural yields and negatively impact agriculture and fisheries on top of displacing people (source). Swift action to slow SLR can reduce the magnitude of these impacts while improving human outcomes.

Further Reading:

Read about how increased flooding with seawater threatens drinking water (source).

Adaptations Needed

In addition to cutting our carbon emissions, we will need to adapt to SLR, and some places have already started. Louisiana, for instance, formed Louisiana’s Strategic Adaptations for Future Environments (LASAFE), a government agency dedicated to addressing and adapting to the challenges posed by SLR and increased storm surges.

In 2017, LASAFE launched a year long community engagement campaign to involve residents, stakeholders, and government officials in selecting coastal adaptation projects. Among those selected were buyouts for homeowners currently living outside of the local major storm protection system, and prototyping resilient, affordable housing for residential construction projects in low flood risk areas.

In the Netherlands, we’re seeing ingenuity in infrastructure that plans for sea level rise instead of trying to hold the sea back. In the city of Rotterdam, parking structures and city plazas have been designed to double as reservoirs during floods. The government is also funding a prototype for floating dairy farms that could reduce greenhouse gas emissions by localizing milk production. This dual purpose solution accommodates local farming in the face of sea level rise while reducing emissions.

Solutions of every size count in low-lying regions, like replacing concrete with native plants and planning cities with public spaces that double as reservoirs. Many other cities, including Bangkok, Beijing, and The Maldives are adapting to sea level rise, and you can read more about their strategies here, from “sponge cities” to floating homes.

Action Ideas and Resources

- Find out if your town or city has an adaptation plan, or a plan to accommodate displaced people.

- Explore the articles linked in this guide to learn more about the widespread impacts of sea level rise and best approaches to limiting the negative impacts on a broader scale.

- Learn about the economic turmoil that could result from coastal mortgage defaults.

- If you are a homeowner in an area vulnerable to sea level rise, find native plants in your area that you could use to make your landscaping more flood resistant.

- Combating sea level rise takes a multifaceted approach to sustainability.

- Learn more about what you can do with on the ClimateMusic action page.